October has started, and the end of the year looms ever closer. Imagine, the end of 2020. As if an arbitrary change in number could make any difference! But well, people like to be hopeful anyway, and who am I to dash their dreams? So let’s focus on what we do best.

October is also a time for Halloween, which is always a good excuse to replay some horror-themed games. My choice for this year was… well, more than one. Call of Chtulhu ended up being better than I originally expected, but still somewhat average. Enemy Zero, which I’m playing again now, is always good for both tension and complete frustration at Laura’s slow pace. You’d think she would act with a bit more urgency, what with murderous aliens very keen on eating human heads roaming the space ship.

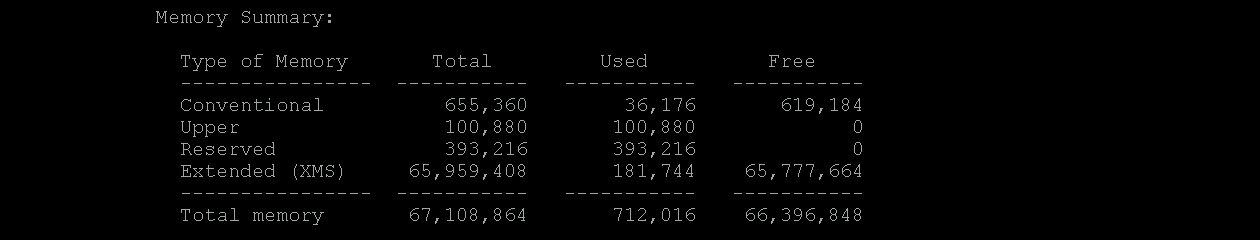

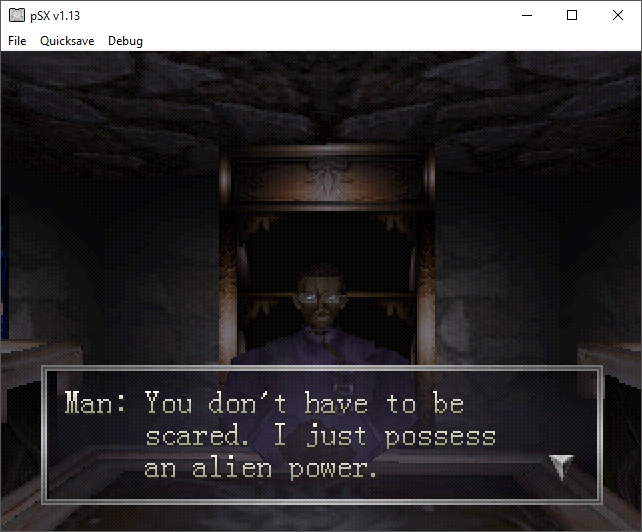

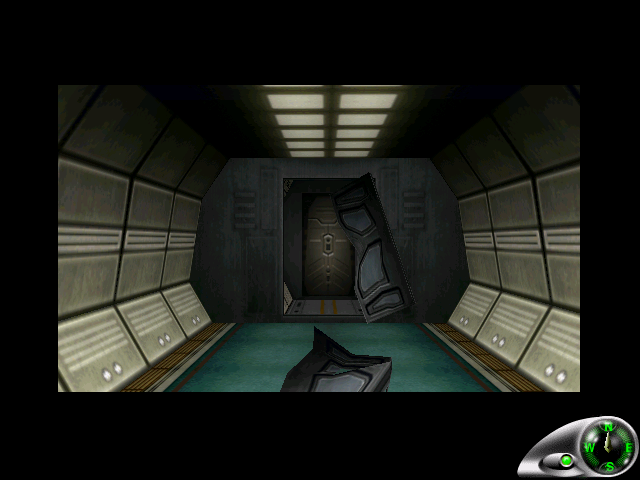

Another game I finished is Echo Night. One of those titles dating back to a time when From Software still wasn’t solely as the Souls guys, it has both a certain charm and a certain jank to it. But there’s something else to it, an attempt to use polygons to do everything. And I do mean everything. The game looks quite ambitious, in spite of its obviously low budget, but sometimes ambitions can’t be matched by technology. In this case, we are talking about, what else, polygons? The PS1 was so good at those. But when you only have polygons, and only a few of them, issues arise.

What I’m thinking here is scale. Maybe it’s not something we think about today, since technology has come along to the point that we can reproduce every scene just about perfectly. Looking weird is not really an issue anymore, although uncanny valley might perhaps be. But in the past, how would one have dealt with the issue of giving the perception of scale?

You’d think first person games would be exempt from this problem: after all, we automatically assume that our point of view is a human-sized being, and perceive everything else starting from that point. Unfortunately, that only creates more problems when we are trying to show something that is, in truth, far bigger. While the solution is to simply put a few “known” objects in plain view, the illusion is nonetheless hard to dispel.

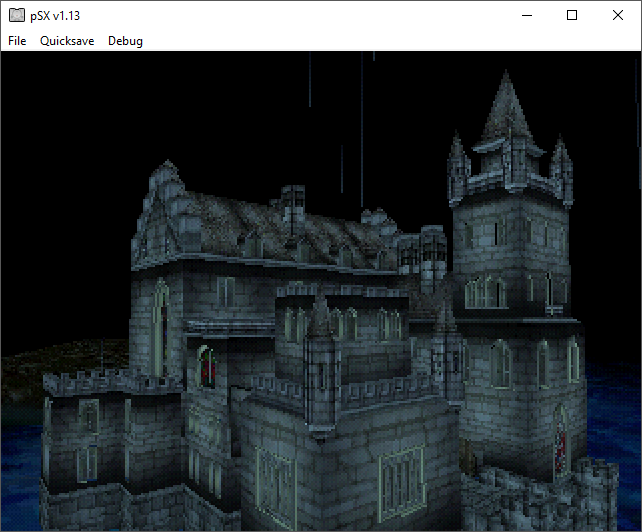

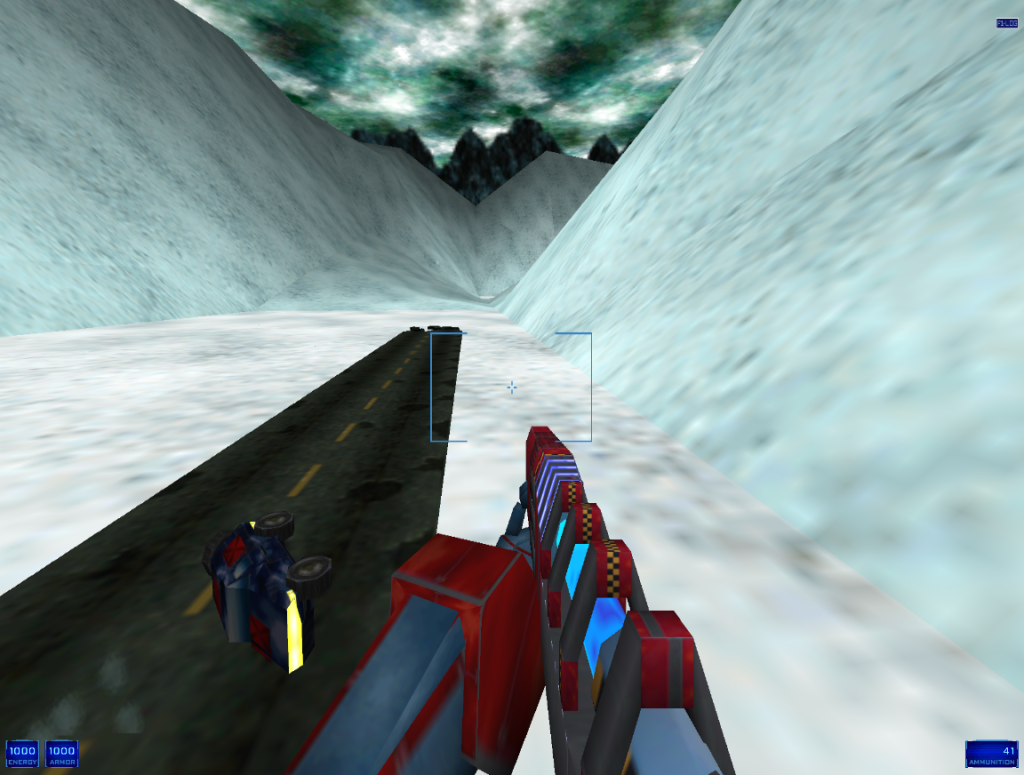

Even moreso because your smaller-looking object have to be done with very few polygons. You might well show a Lego-sized car next to the player character to indicate that you are actually piloting a giant mech, but due to the number of polygons and texture size you could use, the car is going to look like actual Lego, and that doesn’t help.

Another solution might be to rely on different known factors. For example, if you are on a giant mech, employing a mech-like HUD would help reinforce the illusion. Hell, just show the mech in its entirety! But we are just so used to games being human-sized that sometimes it doesn’t matter.

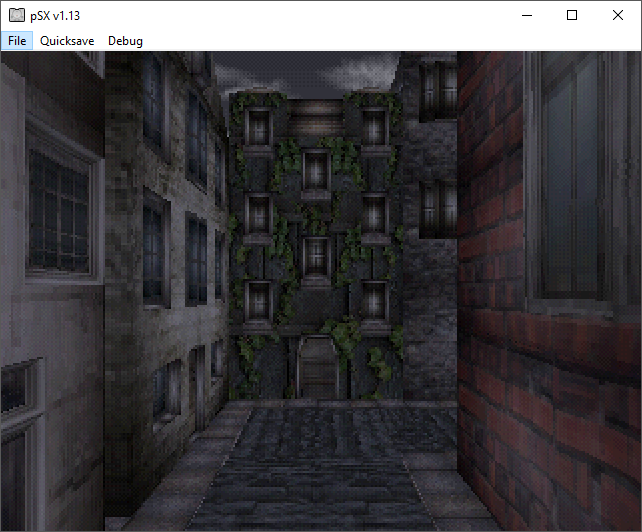

Especially in the past, enviroments were generally limited in what you could render. Oh, you in a city? Well, here’s a few buildings. In a canyon? Have some red rocks. We were so used to these things being in human scale, that when we see them in giant scale, we tend to perceive them as human sized all the same.

Malcolm said in Jurassic Park (the book, not the movie: he didn’t say much of anything in the movie, aside from some memetic lines) that things tend to be the same regardless of the scale factor: a boulder won’t be too different from a mountain, and so on. I think he used it to explain some kind of fractal theory. Well, I don’t know much about quantum maths, but I’d argue he was right. Those big environments don’t look very different from small ones. How we perceived them, however, is a different matter.