I’ve never made a game (ok, I did dabble in Adventure Game Studio for a bit, but I’ll spare you the horror). If I ever made one, I think one of my questions would be… how do I tell people what can be interacted with?

This seems like a silly question, but knowing how to comunicate with the players can’t have always been easy. In the earliest days it was perhaps entirely unnecessary: here’s a line of aliens, shoot them all. But as new genres were introduced, especially adventure games, things got complicated. Sure it would have been nice if you could have used everything to do anything. But I’m afraid it wasn’t a time for Scribblenauts yet. So you had to somehow tell people what they could grab and what was nailed in place!

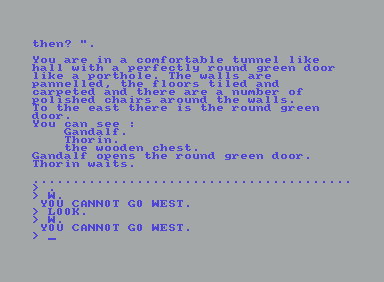

The earliest text adventures might have found their solution, but it was kinda conspicuous to tell people: “you are in a room. There’s all sorts of stuff in here. By the way, look at that piece of garlic on the table”. It makes sense, but why would your character’s eyes fall on the piece of garlic in particular? Maybe he’s hungry. As descriptions in adventure games got a little more flowerish, especially from Infocom, they also got a little better at hiding this practice. But in the end, you do what you gotta do. Things just had to wait until graphics arrived.

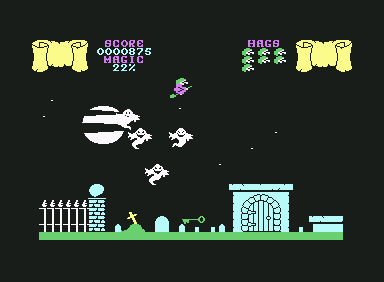

Even so, for a while, I don’t think it was all that important to tell players what was interactive. After all, if you could see it, there were probably two results: either it was bad and you’d die upon touching it, or it was good and you needed to walk over it and get it. Whichever it was, people could (usually) tell by themselves. And if not, well, trial and error always worked.

Adventure games were once again out of luck, as the amount of details in the picture increased. Surely that flower pot is interactive? Nope. And that statue? Neither. But at least in Scumm games there was one concession: interactive items had a small description appear in the interface. At least you were able to finally work out somehow that the hamster could go in the microwave oven. That is probably one of the earliest forms of highlighting. It also resulted in a lot of pixel hunting. Wish they had thought about that.

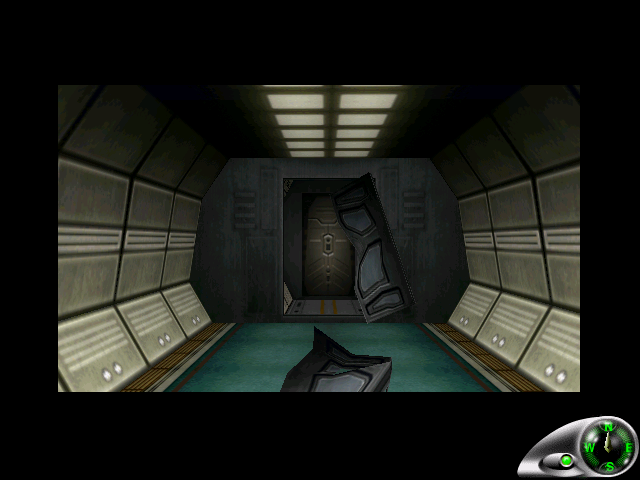

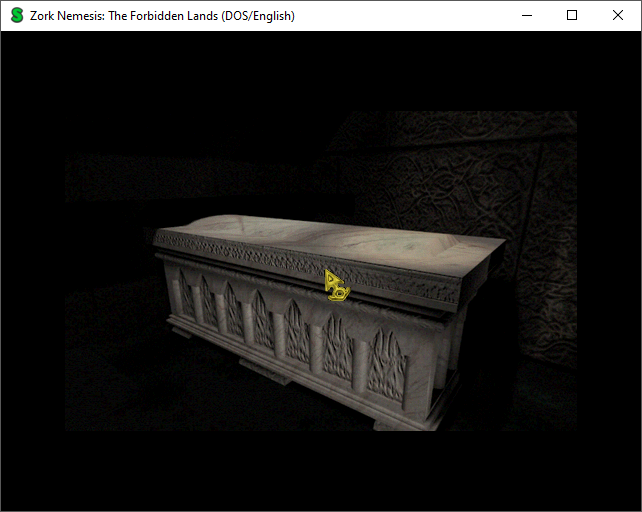

This wasn’t always possible, especially after The 7th Guest and Myst showed the world what you could do without, erm, much of an inventory or even HUD. Aside from underground mazes, I mean. Once again the problem was telling players what could be clicked safely. Why, that was easy: since it needs to be clicked, your cursor has to go upon it. So just change the shape of the cursor! Not you, Lighthouse. For some reason you didn’t wanna do this and I hate you.

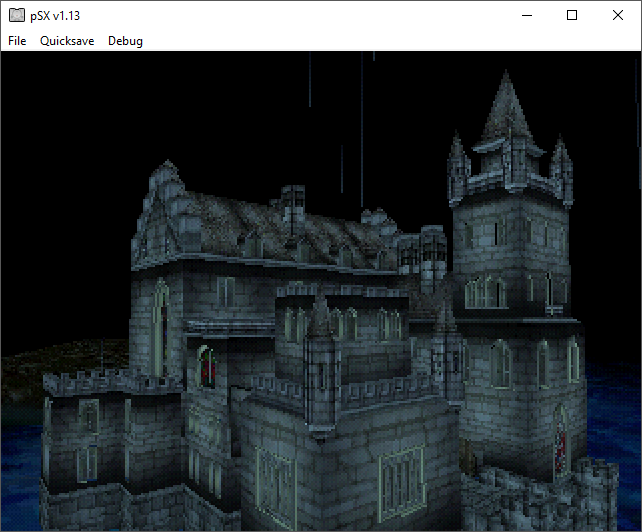

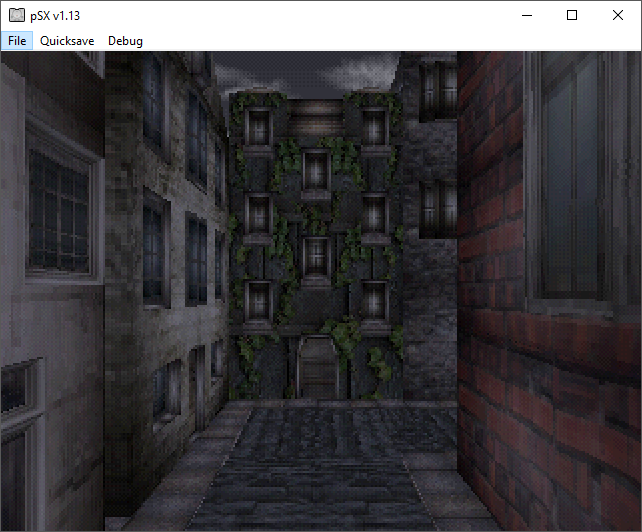

All of this is well and dandy with 2D. But what about 3D? No mouse means you have to find other ways. Well, the earliest 3D games perhaps didn’t need to: for example, in Alone in the Dark, you can be pretty sure that if something is in 3D, it can be interacted with. So that’s one way to do it. Just use common sense there. Although this wasn’t always so. I wonder how many people noticed the books hidden in the library background.

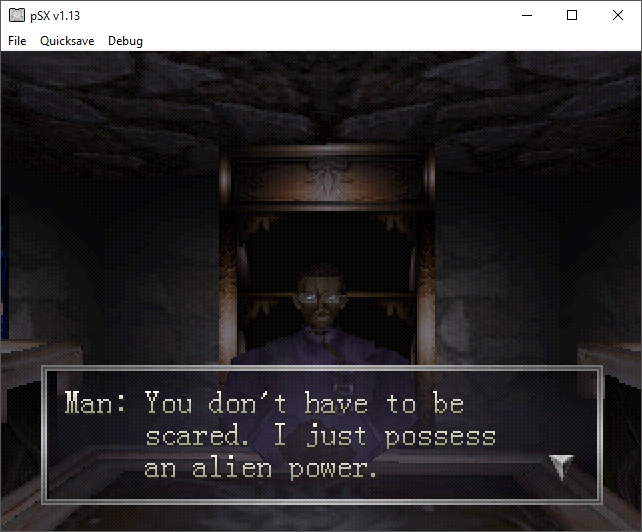

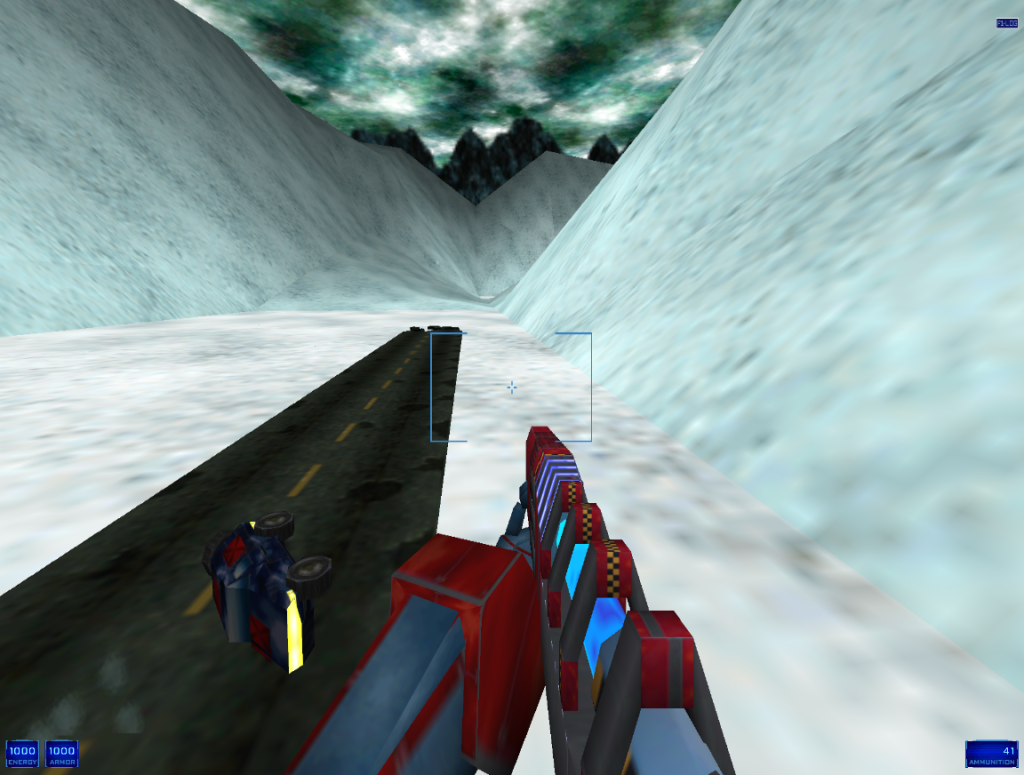

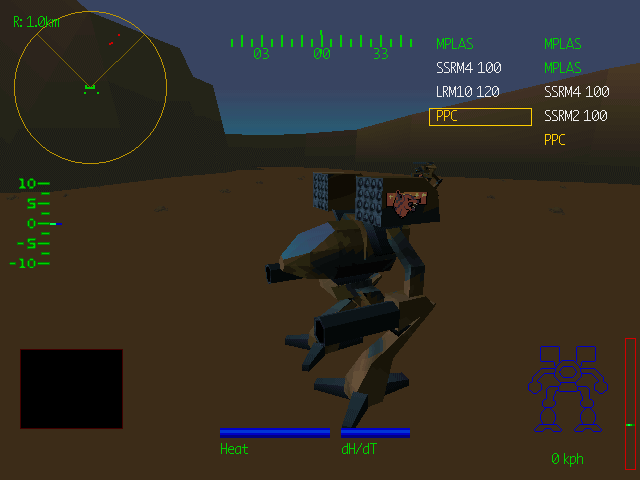

But one day, 3D just had to become ubiquitous. Now eveything was 3D. How do you deal with that? If everything is a model, what should the players check? And, as the amount of details increased, the issue just became bigger. This is the problem we face today: in a world full of details, what are the important details?

There have been a number of solutions so far. Here are some of the most common.

Nowadays, the most common methods used are the highlight, the outline, and the button prompt (the revolving item style has mostly fallen in disuse as games strive for slightly more realism). I can’t quite tell which is the most elegant solution. Highlighted items can be kind of jarring in a dark, moody, survival horror game. And might be unnoticeable in a well lit game. Button prompts don’t help until you are very close to the item in question, besides nobody likes seeing half the screen covered. Flashing outlines, maybe? They are probably my favorite, although this might be just my Serious Sam bias speaking. But even I find them distracting sometimes.

Maybe there’s a better solution out there. After all, games have tried everything, not just the methods I’ve mentioned here. Manny in Grim Fandango tilted his head to any object that could be used or observed (but nobody liked this system). In Lunacy, you just press forward everywhere, and if it does something, good for you. The detective in 2Dark automatically uses any object in range. Not sure that’s very comfortable. Anyway, I know there must be other games out there that did their own thing. If you know of any other examples, drop me a line in the comments.

Who knows, maybe it won’t even be important anymore in the future. Maybe games will be streamlined to the point where the characters will just do whatever they need to do in cutscenes. And if that happens, maybe they won’t just put hamsters in microwave ovens anymore.